Can the Chinese Actually Understand the Japanese and Korean languages?

What are the differences between Chinese, Japanese, and Korean (collectively called CJK, for short)? Are Chinese characters (hànzì) the same as Japanese kanji and Korean hanja?

You are not alone if you are confused. Let’s debunk some of the biggest language myths about CJK.

Myth 1: Japanese and Korean originated from the Chinese language.

No. There is no dispute about their origins; they did not come from the Chinese language. What is a fact is that a large part of their vocabulary consists of borrowed Chinese words, which happened during the countries’ historical interaction with each other. Furthermore, although the Korean language (Altaic) and the Japanese language (Japonic) are highly similar to each other (e.g. similar-sounding words and grammar rules), they are considered to be isolated and different languages too.

Myth 2: Asians who can speak either one of the CJK languages actually understand and/or speak all three of them.

No. A person who knows one CJK language might be able to understand most of the words written on a Chinese/Japanese/Korean newspaper, but not everything. What he/she can do is link enough of the characters together to get a picture of what is probably being written about. As for the spoken word, there may be far too many differences between CJK for one to know what the other person is saying.

What are Chinese characters (hànzì)?

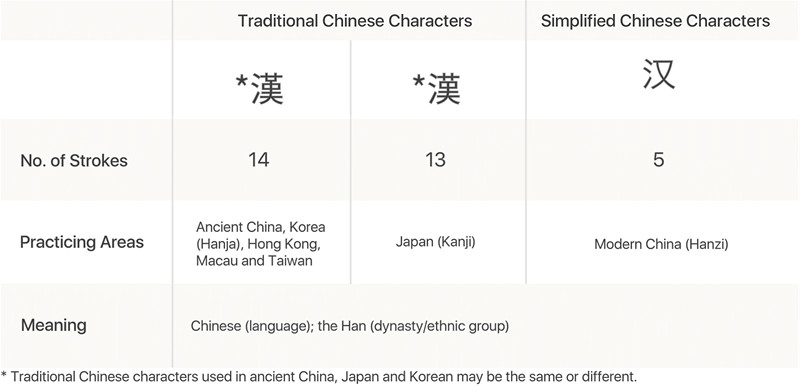

While Chinese characters (hànzì) were developing in China, Japanese kanji and Korean hanja did not exist yet. Eventually,, the Japanese people adopted hànzì to write their own language, which became ‘kanji’. Korean people did the same, and adopted hànzì to write ‘hanja’.

Myth 3: Chinese characters (hànzì) = Japanese kanji = Korean hanja?

No. Chinese hànzì, Japanese kanji,and Korean hanja do not use the same set of traditional Chinese characters.

The characters used in Korean (hanja) and Japanese (kanji) are distinct from those used in China in many respects. First, they look similar (but not necessarily exactly the same) to traditional Chinese characters than simplified Chinese characters. Second, they typically have (but not necessarily) similar meanings, but often quite different pronunciations.

Myth 4: Chinese hànzì, Japanese kanji, and Korean hanja have the same pronunciations

Chinese hànzì and Japanese kanji/Korean hanja are pronounced differently!

For example:

“剑/劍” (“sword” written in simplified and traditional version respectively) is pronounced “jiàn” in Mandarin Chinese but written as “剣” and read as “けん [ken]” or “つるぎ [tsurugi]” in Japanese. It is written as “劍” and read as “검 [geom]” in Korean.

Let’s look at ten more examples!

| English | Japanese Kanji | Korean Hanja | Chinese Hanzi | Kanji/Hanja which has different meanings in Chinese |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| photo | 写真 しゃしん (sha-shin) | 写真 사진 (sa-jin) | **照片 (zhàopiàn) | *写真/寫真 (xiězhēn): photo book/portrait (normally referring to sexy portraits of a model) |

| promise

| 約束 やくそく (yaku-soku) | 約束 약속 (yak-sok) | *约定/約定 (yuēdìng) | *约束/約束 (yuēshù): to restrict, to constraint |

| reservation | 予約 よやく (yo-yaku) | 豫約 예약 (ye-yak) | *预约/預約 (yùyuē) | |

| cooking | 料理 りょうり (ryou-ri) | 料理 요리 (yo-ri) | **料理 (liàolǐ) | |

| feeling/mood | 気分 きぶん (ki-bun) | 氣分 기분 (ki-bun) | *感觉/感覺 (gǎnjué) | *气氛/氣氛 (qìfēn): atmosphere, mood (not feeling) |

| arrive | 到着 とうちゃく (dou-chaku) | 到着 도착 (do-chak) | *到达/到達 (dàodá) | |

| family | 家族 かぞく (ka-zoku) | 家族 가족 (ka-jok) | **家庭 (jiātíng) | *家族 (jiāzú) includes the “immediate family” and other people related by blood or marriage |

| bag | 鞄 かばん (ka-ban) | 가방 (ka-bang) | **包 (bāo) | |

| easy | 簡単 かんたん (kan-tan) | 簡單 간단 (kan-dan) | *简单/簡單 (jiǎndān) | |

| newspapers | 新聞 しんぶん (shin-bun) | 新聞 신문 (shin-mun) | *报纸/報紙 (bàozhǐ) | *新闻/新聞 (xīnwén): news

|

*simplified/traditional

**simplified and traditional characters are the same

Did you notice the high similarities between Japanese and Korean pronunciations? Japanese and Korean share a considerable number of lexical similarities than may not be applicable to Chinese.

The modern way to learn Chinese characters

Nowadays, people can easily write in all three languages by using a phone or computer. It’s possible to learn Chinese characters without writing them out by hand. You just need to learn the Pinyin/Zhuyin and select the right characters, in which most of the time the right characters are chosen automatically. Before phones and computers, one had to actually learn to write them with a pen and paper.

Conclusion:

As with other learning other languages, you need to do a lot of reading, listening, and speaking to become fluent. Learning Chinese characters is a major investment of time, but there is one thing for sure: once you get into these languages, you will see the beauty in them, as well as a reflection of the great culture that created them. These languages will enrich your life in a way that you can never imagine, and give you a deeper understanding of the people who speak them.

Thanks for this writeup, was very helpful in understanding the the concepts. Too bad that learning Hanja doesn’t transfer to Chinese.

This was written long ago but I happened upon it. If you are learning Korean very seriously, or are a native Korean speaker who didn’t study hanja very carefully in school, it will absolutely help you a great deal to learn hanja if you ever wish to learn to *read* Japanese especially but also Chinese. The author is correct that the pronunciation differences of the same characters in difference ‘CJK’ language is too different for knowing one language to help much in understanding the spoken word in the others. However I think she exaggerates a bit how different the characters are in the three. The character sets used in Japanese and Korean are the same for most characters, and the ones that aren’t don’t take that long to pick up. Simplified Chinese is much more different but the traditional set used in Taiwan and by overseas Chinese is virtually the same as the Korean set. Meanings are different but a pretty small % of the time. I have been able to learn to read Japanese reasonably well and (traditional character) Chinese somewhat by knowing hanja with a small percentage of the effort it would take starting from scratch. Of course in Japanese you must also learn kana but that’s nothing like the task of learning 100’s of characters. Also not mentioned in the article, many ‘Chinese derived’ words in Japanese were coined in Japan and then absorbed into Korean in the colonial period (1910-45), some made their way into Chinese usage. On certain subjects (for example 20th century military history, a special interest of mine) technical terms are almost all the same in Korean and Japanese.

Exactly! A large portion of ‘Chinese words’ (pronunciation) are actually Japanese and originate in Japan

Through reverse travel and trade, Korean absorbed many Japanese words and consequently into Chinese. Chinese often make the mistake to assume that most words originate in China, this is false. Japan has been a pioneer in over 10% of Chinese vocabulary and pronunciations – this is called the Sinification or Sinofication of words (meaning adopt into Chinese by using native sounds and pronunciation). And because of this, it is often ignored and passed off as Chinese

Thank you very much for your helpful information! I think I am getting interested in learning one of these languages for cultural purposes!

Great write up! However, the theory that Korean is an Altaic language has been debunked. In the academic linguistics world, it is defined as a language isolate, and it’s roots are simply the Koreanic language family.

👍🏾

How does one borrow a letter? The Chinese language is the foundation of both the Japanese and Korean language. Even the words you picked out to show us the difference in the writing is off by one or two stroke but is at the right place. The rest of the so call borrow letters are the same to the Tee and all means the same..

No, sir. Please allow me to correct you before making any further ignorant claims so that no-one is misled into thinking similarly. Chinese is NOT the foundation of these languages.

Japanese and Korean are their own languages; these words had applied meanings since the beginning of these cultures. They existed long before the existence of modern Hanzì and were believed to have their own scripts in their native ancient civilisations which were not too popular and became lost. A similar story exists in Arabia – many who did not have wealth were unable to be taught the Arabic script and known as illiterates. Only fortunate and rich people were able to be schooled. The same applies to Japan, because majority people were farmers, textile or blacksmiths, artisans or singers; because they were quite poor they could not be taught or schooled the native writing scripts that were taught to the few royals and nobles for communication. Over time there were many wars and destruction (burning of palaces, schools, vaults) so it all got burned down, erasing it from the national mind as most people did not know it. Likewise if Arabs who taught or learned their scripts became fewer, over centuries and a thousand year(s), it is bound to be forgotten in the sea of sand.

These are mere strokes in characters. They themselves do not justify the language, only to hold a meaning when used in conjuction to words. Japanese itself for example is much more complex than Chinese, as all characters would have a base of 3, 4 or 5 readings and can even go beyond 7. Chinese is concrete and the most difficult part is simply a consistent pronunciation to not differentiate it with different words of similar intonations. Other than that it is merely remembering the strokes of each character. The writer was not trying to show different writing but different pronunciation: the Chinese being different from the other two and the Korean pronunciation originating from the Japanese. Most Chinese combinations differ as that is the only script. In truth, the origin of Hanzì is a mystery as the Chinese invaded many nearby regions (Tibet, East Turk, etc.) and the major contributors to the Chinese dynasties and culture were the Mongolians as well as the influence they brought along, and later added South Mongolia.

In the end, Asian languages from the Near East onwards are usually difficult for 98% of westerners, of whom try to simplify these complex languages in a manner befitting to them without realising that they are corrupting stylisation and choice of the native people. For example, Jp character can be pronounced both “T” and “To” with the latter being the prime in native words. The problem is westerners only oversimplify it to the latter without understanding as the language holds little specific tones, it can legitimately be written in many different ways without being cringy.

I hope that clears any underlying confusion and misunderstanding 🙂

This is a nice introductory article for non-linguists who would like to know what distinguishes these three completely unrelated languages. However, there is at least one glaring inaccuracy and one very misleading point in what you have written. The first concerns your explanation in the “Myth 2” section. The assertion that “CJK” speakers can read each other’s printed materials is absolutely incorrect. While Japanese people might be able to decipher a simple Chinese phrase or document (because both written languages make use of semantically similar characters), the opposite is less true. Furthermore, Koreans use a completely different writing system that is not mutually intelligible with the other two in the “CJK” trio. Korean hanja are not studied to the same extent by the whole population that Japanese kanji are.

“CJK” appears to be your made-up acronym, by the way.

Finally, underneath your table you claim that “Japanese and Korean share a considerable number of lexical similarities than may not be applicable to Chinese”, but you fail to mention that most of those words have a common origin in Chinese. They were borrowed from Chinese into the other two languages, hence their similarly. Also, “kaban” handbag is originally a Japanese word that was borrowed into Korean. When discussing relationships between vocabulary in different languages, it is VITALLY important to distinguish between loans and cognates.

You claim to be a linguist but have never heard of CJK?

The Korean language is more related to Southern Chinese dialects like Cantonese, Hakka and Hokkien in terms of pronunciation. Mandarin is a Northern dialect and sounds distinctly different from Southern dialects. Southern Chinese dialects(Same as Korean and to an extent, Japanese) has a lot of words that either start with a k….. or ends with a …..k sound, something which is very uncommon to Mandarin words.