Chinese: A Language of Compound Words

At first glance, learning Chinese characters can seem intimidating. And it can be a difficult task, especially if you try to memorize them one by one like many teachers force students to do. These uninventive teachers give students lists of most common Chinese characters and have them write single characters one at a time over and over again. However, learning the symbols in this way, removing them from their context, is tiresome: especially in the early stages of learning.

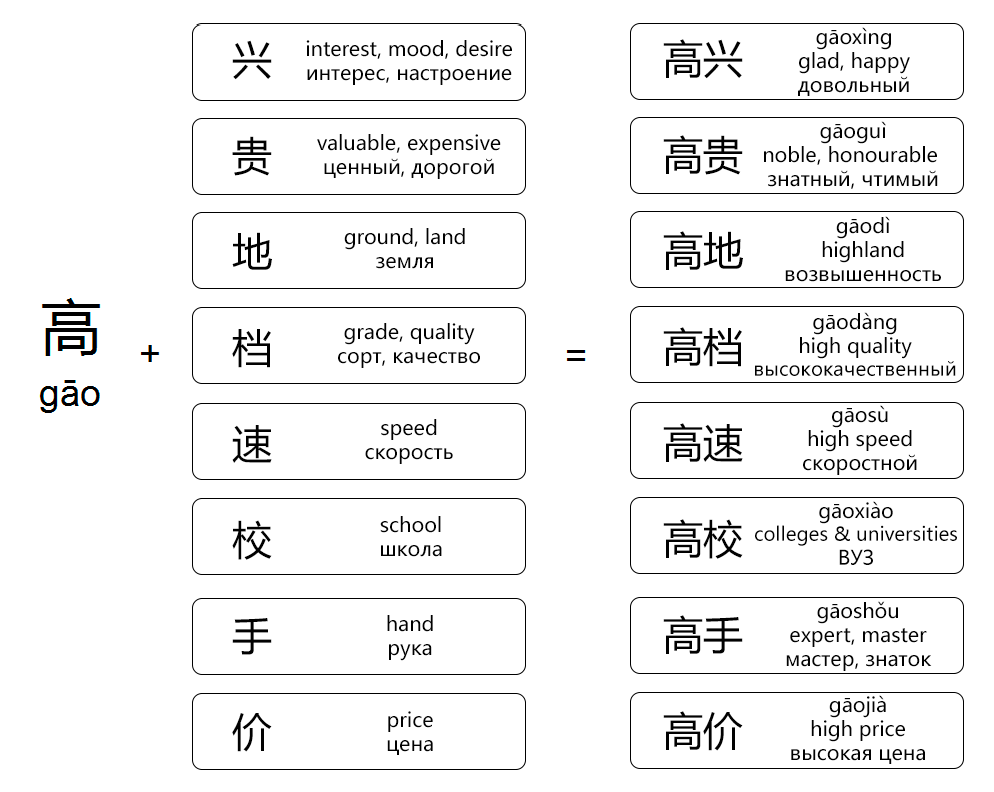

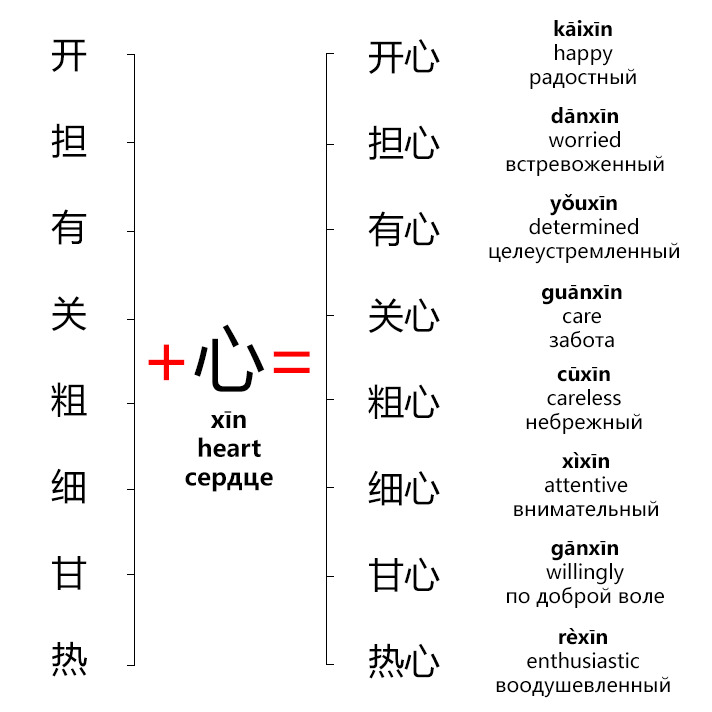

Thankfully, there is a clue that is often missed by beginner-level learners: Mandarin Chinese has a ton of compound words! Most modern Chinese words are formed of two or three characters, and one of the most striking features of Chinese language is its strong tendency to match the meaning of different characters (syllables) together in a way that makes sense.

Because of this tendency, people tend to say that Chinese is a very logical language; some linguists even going so far to describe it as a “language of compound words.” Not all Chinese disyllabic (two character) words behave logically (their precise classification is still a topic of debate), but in general, this unique “character-matching” trait of Chinese language can really help a new student learn the language!

Below you can see examples of 3 types of compounds: subordinate, attributive and coordinated.

In subordinate compounds, one word clearly subordinates (or supports) another. There are many ways in which the subordination can manifest itself:

- 房型 – fáng xíng – layout of house (house + model)

- 楼花 – lóu huā – building that is put up for sale before it is completed (floor + to spend)

- 监事 – jiān shì – supervisor (supervise + matter)

- 攀高 – pān gāo – to rise (climb high)

In attributive compounds, the descriptive character precedes the noun/verb:

- 天价 – tiān jià – high price (sky + price)

- 婚介 – hūn jiè – matchmaking (wedding + to introduce)

- 速递 – sù dì – express delivery (fast + to pass)

- 互动 – hù dòng – interaction (mutual + to move)

In coordinated compounds, all the characters are equally important in determining the meaning. The bases tend to indicate things of the same class or kind.

- 蔬果 – shū guǒ – vegetables and fruits (vegetable + fruit)

- 警示 – jǐng shì – warning (warn + show)

- 高矮 – gāo’ǎi – height (high + low)

- 亮丽 – liàng lì – very beautiful (bright + beautiful)

Conclusion: A more traditional approach to learning Chinese characters, learning each character as a stand-alone entity, will slow down a beginner’s acquisition of the language.

By taking advantage of the fact that the vast majority of Chinese morphemes have a lexical nature, and memorizing characters as parts of compound words, students can learn more efficiently. Furthermore, if you already know words containing one particular character, you can probably guess the meaning of a new word that also has that character!

The article is great and matches what I am discovering as I study Chinese. Would you happen to have a recommendation for a book or study guide that organizes words by compound to make it easier to learn related vocabulary?

I am helping a Chinese friend edit her book about growing up in China. One issue has been whether to “push” pinyin words together for Chinese names and short words, e.g., Mao Zedong or Ayi.

She also provides Chinese characters whenever she uses a a Pinyin word, e.g., Ayi (阿姨) or Lin Yue-jiang (林越江).

However, we have not figured out what to do about pushing the pinyin words in a Chinese phrase like “Going through the backdoor.” Do you think we should write zou hou men or Zouhoumen?

Tony