Cracking the Wisdom of Chinese Idioms

Here are two facts about Chinese idioms: there are lots and lots of them, and for the most part they are not particularly useful.

I’ve been a student of Mandarin Chinese for 20 years. It’s one of the languages my wife and I use with our kids, and I can tell you that I rarely use idioms — or proverbs, or adages – or whatever you call these compact expressions.

Yet, there is a beauty in the way they distill the human condition into a string of four (or five or six) syllables. If you like cultural trivia and the rhythmic poetry of (any) language, there’s a good chance that you’ll get a kick and a laugh out of these.

一石二鸟 (一石二鳥)

one stone, two birds

(Yī shí èr niǎo)

I think this expression is a good jumping-off point for this topic because of its familiarity and simplicity. Did the English saying “Kill two birds with one stone” come directly or indirectly from this Chinese idiom? I will leave that up to language historians. The meaning and the imagery are the same for both languages.

虎头蛇尾 (虎頭蛇尾)

tiger head, snake tail

(Hǔ tóu shé wěi)

In expressions involving animals, some beasts tend to represent positive and virtuous qualities, e.g. the tiger, the horse, the dragon. Others, like the pig and the snake, are typically associated with negative, undesirable ones. This contrast is on full display in this case, where “tiger’s head, snakes’ tail” implies a strong start but a weak finish.

骑虎难下 (騎虎難下)

difficult to dismount a tiger

(Qí hǔ nán xià)

To be in a precarious, sticky situation with no easy escape. To be in over your head, or perhaps beyond the point of no return.

I love that the next two use drawing as an analogy. It seems appropriate for Chinese script, with its highly graphical, three-dimensional representation.

画龙点睛 (畫龍點睛)

draw dragon, dot the eye

(Huà lóng diǎn jīng)

To add the finishing touches to something, literally to dot the i’s and cross the t’s. It can also refer to making a final point that caps a strong argument and closes the case.

画蛇添足 (畫蛇添足)

draw snake, add legs

(Huà shé tiān zú)

To ruin something by adding what is superfluous, to embellish, to overdo.

对牛弹琴 (對牛彈琴)

play the lute to a cow

(Duì niú tán qín)

The reference here is speaking to or performing for an unappreciative audience, i.e. speaking to a wall, preaching to deaf ears. The slight is not intended for the proverbial cow, but for the speaker or performer who misjudges his audience.

鸡同鸭讲 (雞同鴨講)

chicken talking to the duck

(Jī tóng yā jiǎng)

This describes a failure to communicate — a scenario where two parties are not on the same page, and talking past each other.

狗嘴里吐不出象牙 (狗嘴裡吐不出象牙)

ivory will not come from a dog’s mouth

(Gǒu zuǐ lǐ tǔ bu chū xiàngyá)

Truthful or refined speech will not come from the mouth of a crude individual.

卧虎藏龙 (臥虎藏龍)

crouching tiger, hidden dragon

(Wò hǔ cáng lóng)

This phrase is immediately recognizable from the Ang Lee movie of the same name, but what does it mean? For a long time, since martial arts featured prominently in the movie, I assumed that the expression referred to kung-fu positions. In fact, it is used to describe individuals with hidden talents and unexplored potential.

Here are some of my personal favorites.

脱裤子放屁 (脫褲子放屁)

drop pants to fart

(Tuō kùzi fàngpì)

I love the visual that this projects for the mind’s eye. The meaning is to make things overly complicated, to exert unnecessary effort. A close match would be crossing a river to get water, or a tortuous and convoluted sequence of steps that we might describe as a Rube Goldberg process.

笑里藏刀 (笑裡藏刀)

dagger concealed by a smile

(Xiào lǐ cáng dāo)

Friendly manners belying sinister intentions — a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Notice that this phrase uses the same complicated but very attractive character 藏 as the previous, meaning “concealed, hidden”.

久病成医 (久病成醫)

long ill, become doctor

(Jiǔ bìng chéng yī)

A prolonged illness turns the patient into a medical expert — pretty self-explanatory.

占着茅坑不拉屎 (占著茅坑不拉屎)

occupy the latrine but not shit

(Zhànzhe máokēng bù lā shǐ)

Yes, Chinese sayings can get graphic too. The idea of someone hogging and preventing access to a resource that he himself has no use for pops up in Western tradition also — in the fable of the Dog in the Manger. And another colloquial expression comes to mind: Shit or get off the pot!

Let me conclude with another personal favorite. As much as I like idioms featuring animals, I have an even stronger affinity for phrasing that attributes human qualities to inanimate objects.

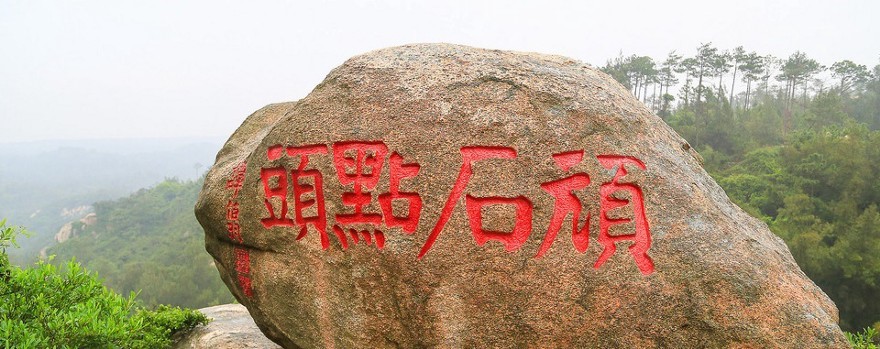

顽石点头 (頑石點頭)

stubborn rocks nod their heads

(Wán shí diǎntóu)

This is used as a compliment, for an argument so persuasive that even the rocks and stones (or the more dim-witted members of the audience) can’t help but to nod in agreement.

Many Chinese idioms and proverbs are derived from some fable or legend — they are abbreviated forms of a longer backstory. This particular phrase is traced back to a Buddhist monk named Wei, from the Jin Dinasty (4th and 5th centuries, A.D.). For me it is also tied to a memorable experience, from the time that I visited Taiwan’s amazing Kinmen island, and saw the inscribed rock atop its tallest peak.

This Post Has 0 Comments