How to Learn Chinese While Remaining Sensitive to Regional Languages and Dialects

Editor`s Notes:

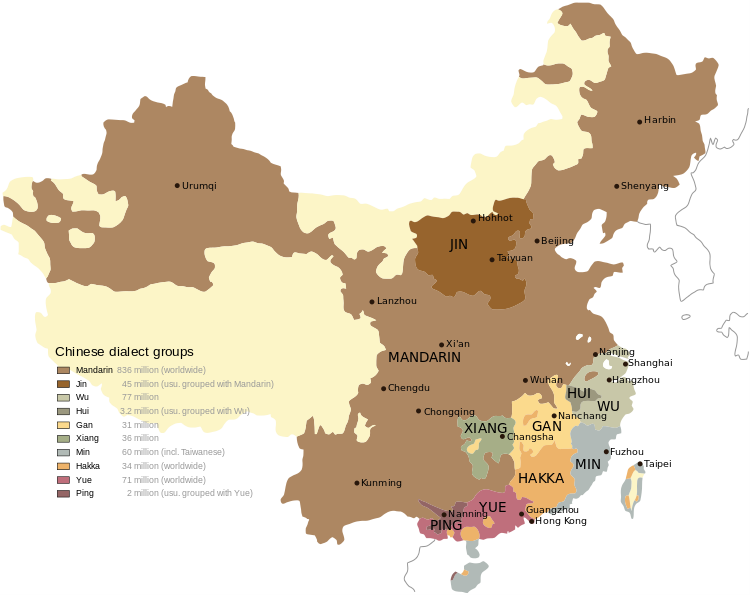

The modern Chinese dialects are classified into seven major groups, and Mandarin (普通话) is the e standard foundation language. About two-thirds of Chinese people speak Mandarin as their first language, which covers all of north and southwest China. Some dialects, such as Cantonese and Hakka, can sound like totally different languages from Mandarin; in fact, these dialects are often treated as such. In addition, in many countries’ Chinatowns, the emigrants there speak Cantonese and Hakka. Foreigners who encounter these dialects often feel confused and frustrated because they are so different from standard Mandarin. However, most Chinese, especially the younger generation, can speak and understand Mandarin without any problem, whether Mandarin is their first language or not. If you intend to learn Chinese, it is still recommended to learn Mandarin first.

Editor in Chief | Cao Jing

To learn Chinese is an experience unlike any other language that I have studied before. I’ve spent two years digging into this ever-more complex pile of vocabulary, slang, and sentence structure and yet, somehow, I only recently realized that no teacher or professor has ever actually defined “Chinese.”

As students, we’re told that we are learning Putonghua or the “Beijing Dialect,” but no additional details, besides the difference in pronunciation. It adds to the idea that “Chinese” is just this monolithic block of Beijing-dialect speakers, but that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Linguistically speaking, the line between a language and a dialect is blurred, eluding a clear definition for professional linguists, let alone a more casual researcher like me. The block of language families that make up Sinitic languages, for example, does include Mandarin, but also Shanghainese, Cantonese, Taiwanese, and almost every other regional variant from Heilongjiang to Hong Kong Island.

So, maybe Putonghua is a good enough shorthand for us to begin to grasp the complexity of the linguistic reality in China. Maybe it is the most useful, being the lingua franca, the link bridging each dialect together, one that helps a traveler or student see a more cohesive whole.

But are we missing something by using that shorthand? What could we gain as learners and cultural observers if we dared expand our classes to include Guangdong hua or Shanghainese?

It’s a question I have a bit of experience with. While studying French in the past, I went to live in a small city in the western reaches of France, where the countryside juts off into the English Channel. They brought us there specifically to learn French, away from the prying eyes of English speaking tourists clogging the streets of Paris and Nice.

People there spoke natural French, exactly as people here speak natural Mandarin. But, the language that was native to the area was a dialect called Breton, which was more closely related to Welsh than French. Over the last century though, Breton had started to disappear, as parents realized their kids had a better chance out in the world being native French speakers. Breton offered them no such wider advantages.

There is a similar phenomenon happening in Shanghai, according to Sixth Tone. Children go to school and are educated in English and Mandarin, and are sometimes prohibited from speaking Shanghainese at all during the school day. People claim that the Shanghainese language, part of a different sub-family of Sino-Tibetan than Putonghua, is dying out as a result.

Once I really began to explore the relationship of that small region to its ancestral language, I became increasingly aware of the fact that I would be missing out on small bits and pieces of culture without it. It helped me to not only understand the place within a particular historical context, but to also form a deeper connection to it, as evidenced by this similar story, continents and years later.

Is there something missing from our time in China if we don’t speak Sichuanese while trekking the peaks near Chengdu or Hokkien while wandering the tulous in Fujian? I honestly can’t say for sure either way, but there most definitely could be something missing.

What I can say for sure is that the one time I went with fellow Dig Mandarin contributor Rachel Deason to get some photos framed in an art shop near People’s Square, the proprietor started speaking Shanghainese, laughing as we tried to parse out his meaning. He asked if we could understand Shanghainese before eventually switching back to Mandarin despite our best efforts to interpret his words. It was a simple conversation on a hot summer afternoon, not a lot in the grand scheme of things – especially in a city that moves as fast as this one. But when we left, I kept wondering how the rest of that afternoon would have gone if we’d known just a bit more Shanghainese, what experience we might have had, or perhaps even made a friend of that octogenarian shopkeeper. Those are the kind of moments I don’t want to miss the next time they come around.

And that’s why I’m going to start learning “Chinese”…again.

This Post Has 0 Comments